U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Proposes National Drinking Water Standard for Six PFAS Compounds

On March 14, 2023, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) announced a proposed National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR) for six per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (“PFAS”). PFAS are a category of manufactured chemicals that have been widely used in a variety of industries and consumer products since the 1940s and many are still in use today. In the last five years PFAS contamination has emerged as a growing environmental concern. In October 2021, the EPA announced its PFAS Strategic Roadmap to address PFAS contamination in water, soil, and air. Pursuant to this Strategic Roadmap, in June 2022 the EPA proposed non-enforceable health advisory limits for PFAS in drinking water. The EPA’s recently announced pre-publication version of the rule attempts to address PFAS contamination by setting enforceable maximum levels of PFAS allowable in drinking water provided by public water systems.

What PFAS Compounds are Impacted by this Proposed Regulation?

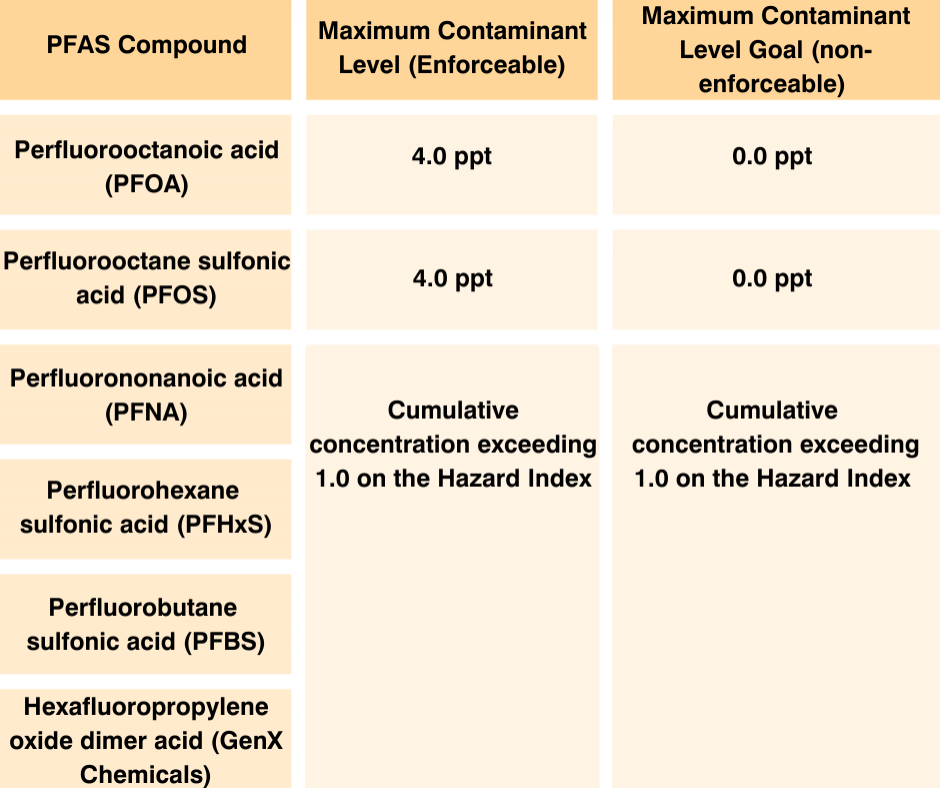

The EPA’s proposal regulates six PFAS compounds known to be found in drinking water, including two of the most prevalent, PFOA and PFOS. The proposed regulation creates two sets of drinking water standards for these six compounds. The first standard creates legally enforceable Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs). This enforceable standard governs the maximum amount of each PFAS compound that can be present in drinking water provided by a public water system.

The second standard creates non-enforceable health-based Maximum Contaminant Level Goals (MCLGs). The MCLGs set the amount of each of the six PFAS compounds that can be present in drinking water at a level where there is no known negative health effect. These standards are not legally enforceable.

What are the Proposed Limits for the Six Identified PFAS Compounds?

For PFOA and PFOS, the EPA has proposed a maximum allowable level of 4.0 parts per trillion (ppt). For the remaining four PFAS compounds, the EPA proposes a different approach using a tool known as a “Hazard Index.” The Hazard Index is a risk management tool that uses a ratio to estimate the potential negative health impact of a mixture of chemicals. To determine the Hazard Index, public water systems would have to measure the concentrations of PFNA, PFHxS, PFBS, and GenX Chemicals in their system and then divide this value by a Health Based Water Concentration (HBWC) that has been set for each PFAS Compound: PFNA (10.0 ppt); PFHxS (9.0 ppt); PFBS (2000 ppt); and GenX Chemicals (10.0 ppt). Once this ratio (also known as a “hazard quotient”) has been established, the ratios for each of the four PFAS compounds are added together to create the Hazard Index. The proposed rule requires that Hazard Index for PFNA, PFHxS, PFBS, and GenX is less than 1.0. The EPA has identified 1.0 as both the MCL and MCLG because a Hazard Index of greater than 1.0 indicates a negative health impact (establishing the MCL), but treatment to below 1.0 is considered feasible (establishing the MCLG).

As set forth in the pre-publication version of the proposed rule, the EPA has proposed separate MCLs for PFOA and PFOS because there is data supporting the conclusion that the level at which there are no known health effects is zero. The EPA can therefore set the MCL to the lowest feasible level of detection. This is not the case for PFNA, PFHxS, PFBS, and GenX, which is why the EPA has relied on the Hazard Index approach to assess the cumulative health risk of a mixture of PFAS compounds.

What Other Obligations Does the Rule Impose?

In addition to dictating maximum allowable amounts of each of the six PFAS compounds, the proposed rule would impose three additional obligations on public water systems.

First, the rule would require public water systems to monitor their drinking water to ensure it does not exceed the identified maximum contaminate levels. A public water system must complete an initial monitoring assessment within three years of the rule becoming effective, followed by quarterly monitoring thereafter. Public water systems may be eligible for reduced monitoring if they can demonstrate that the level of PFAS in the system is at least one third of the MCLs. In other words, that PFOA and PFOS levels are at least 1.3 ppt and the Hazard Index for PFNA, PFHxS, and Gen X chemicals is at least 0.33.

Second, public water systems would be obligated to notify the public if they detected any of the six PFAS compounds in amounts above the allowable maximum. Third, the rule would require public water systems to treat, or otherwise take action, if its water supply exceeded the maximum contaminant level for any of the six identified PFAS compounds. The agency has identified the following best available technologies for treatment: granular activated carbon, anion exchange, and high-pressure membranes.

When Would the Rule Become Effective?

The first three years following promulgation of the rule would include agency activities such as implementing state regulations, training state and public water system employees, and updating and reviewing data monitoring systems. Compliance actions for public water systems would not begin until three years after promulgation of the rule. The rule would also allow a state or the EPA to grant an extension for up to two years for a public water system to comply with the MCLs. Extensions are based on individuals needs and the timing of any improvements that a system may need to undertake for compliance.

Is the EPA Requesting Comment on the Proposed Regulation?

The EPA is requesting public comment on this proposed regulation. The proposed rule has not yet been published in the Federal Register, however, once it has, public comment will remain open for sixty days. The EPA is also hosting a virtual public hearing on the proposed rule on May 4, 2023. If you have questions or would like additional information on this proposed rule or submitting comments, contact Mathew Todaro or any other member of the Environmental & Land Use Group.