Does That Avatar Really Like That Brand? The FTC Endorsement Guidelines in the New Age of Virtual Influencers

She has 1.2 million Instagram followers: She's modeled such famous brands as Diesel, Versace, Fendi and Chanel. In March, she appeared in a fashion spread in V Magazine as "The Face of New Age Logomania." Last month she talked her audience through the latest GIF sets from Prada in Milan.

She has 125k Instagram followers. Last week she finished a fashion editorial for Women's Wear Daily. She came to attention when Fenty (Rihanna's beauty line) reposted an image of her wearing its lipstick, which received an astounding 222,000 likes on Instagram.

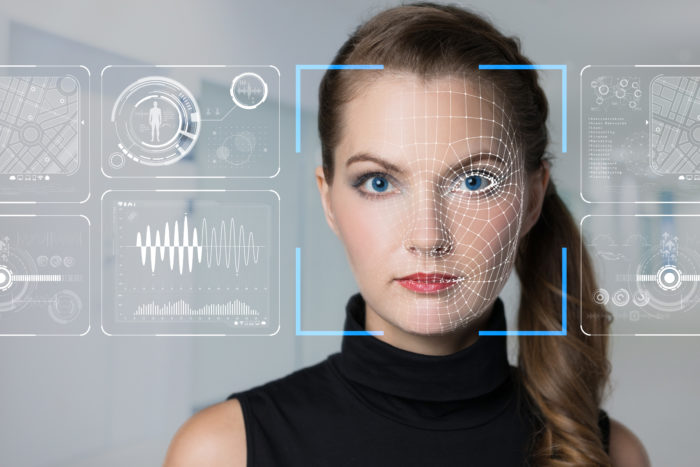

But don't try to meet these models in person. They're avatars. Computer generated images (CGI). Designed by artists and built by computers. But they can strike a pose and sell products almost as well as any flesh and blood supermodel.

CGI influencers present the common situation where the law cannot keep up with technology. The first traffic laws came after the first automobiles. The state of Georgia initially classified cars as "ferocious animals." By the 1920's there were over 130,000 cars on the road trying to cope with the mayhem of some laws requiring driving on the right, while others on the left; and different traffic signs and signal lights in different cities. Today, the government is trying to figure out how to deal with the latest technology -- self-driving cars. Bob Iger, Mickey Mouse's step-father, has said, "The heart and soul of the company is creativity and innovation." And, oh boy, have virtual influencer models become a creative and innovative way to keep lawmakers on their toes.

The FTC's Revised Endorsement and Testimonial Guides define an endorsement as "any advertising message … that consumers are likely to believe reflects the opinions, beliefs, findings, or experiences of a party other than the sponsoring advertiser … The party whose opinions, beliefs, findings, or experience the message appears to reflect will be called the endorser and may be an individual, group, or institution."

Further, "When there exists a connection between the endorser and the seller of the advertised product that might materially affect the weight or credibility of the endorsement (i.e., the connection is not reasonably expected by the audience), such connection must be fully disclosed."

But, the virtual influencer is not "an individual, group, or institution" and she cannot have "opinions, beliefs, findings or experiences." So does that mean that the use of virtual influencers escapes the disclosure requirements under the Guides? Maybe.

But what about the person who creates the avatar, can he/she be an influencer/endorser subject to the Guides? It's not his/her opinion or experience that is being professed.

And is the connection between the virtual influencer and the brand already evident to consumers because the consumer may be able to tell that Lil' Miquela isn't real?

Like the cars v. traffic laws dilemma, the Guides may not have caught up with CGI influencers.

But what about good old reliable deceptive advertising? Section 5 of the FTC Act prohibits "a representation, omission, or practice that misleads or is likely to mislead the consumer" Courts have held that deceptive visualization can be actionable, such as posting pictures of the results of product use that are not accurate. There are also some famous lawsuits involving the use of celebrity avatars in advertising/commerce. In 2012, the band No Doubt sued the maker of the video game Band Hero for using computer generated images of them performing songs for players to rock out to. In 1999, the actor Dustin Hoffman sued a magazine publisher for creating a computer generated image of him from the movie Tootsie wearing a fashion designer's clothes. The picture did state "Dustin Hoffman isn't a drag in a butter-colored silk gown by Richard Tyler and Ralph Lauren. Hoffman was originally awarded $3 million, but the Ninth Circuit reversed holding that the publisher was protected on First Amendment grounds. A recent law review article took the position that "all CGI's of deceased celebrity endorsers fall short of the FTC standards for endorsements" because the FTC Guides provide that "the endorser must have been a bona fide user of [the product] at the time the endorsement was given."

Dead celebrities, real rock bands turned virtual and Dustin Hoffman in drag only scratch the surface of what may be acceptable in virtual reality influencer marketing. We really don't have a clear legal answer on how to disclose, if necessary, any message that the person you're seeing isn't a person and has no opinion about this product.

Some brands may just rely upon the fact that, for now, CGIs cannot be influencers under the law and that a person isn't deceived when an avatar is pushing its product. Other brands may want to at least disclose that you're seeing an avatar. Until (god forbid) more regulation is imposed, brands may just have to use their best judgment, like the drivers of yore trying to maneuver without any rules of the road.

Meet Lil' Miquela.

Meet Lil' Miquela.